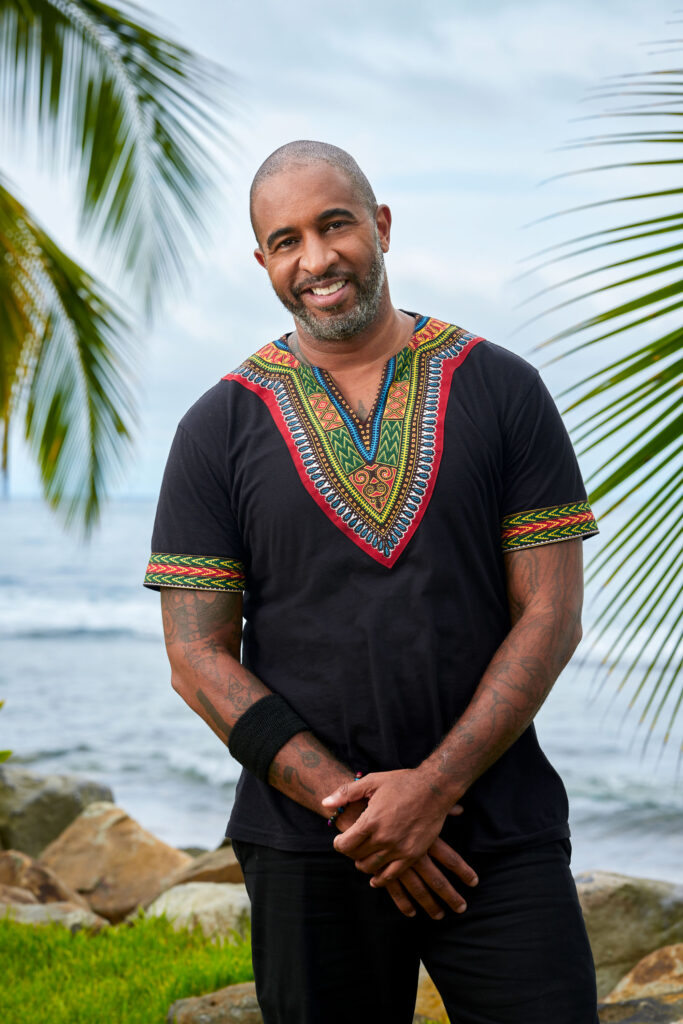

Free World Bound is a program created by Prism Health North Texas. This organization is designed to help incarcerated individuals who are living with or at risk for HIV. Participates can be provided HIV prevention services and be connected to medical care so they can flourish in the free world. This program doesn’t stop at health treatments, but also helps with housing, employment, and many other fields. I’m excited to announce that the organization was interested in a conversation about what they do in the local area. I’ll be speaking with Daron Kirven, the senior director of community outreach, about what locals need to know about HIV in local jails. I will also be speaking with the program’s managers, Allison Boyd and Nadia Mitchell, for further comment on the biggest issues facing to recently released inmates.

Were you guys doing nonprofit work before the idea of Free World Bound appeared?

Daron: Free World Bound is a program underneath Prism Health North Texas. Prism Health North Texas is the actual agency and Free World Bound is a program under the umbrella of Prism Health North Texas. We started the Free World Bound program because of some funding that we received around 2001 while the agency was working with the reentry population. There was a grand opportunity through the Texas Department of Health and that grant was to identify HIV positive inmates prior to release and get those individuals on the HIV drug assistance program. Our team would then assist them with linking up to care once they get released from prison. Since 2001, we have been fortunate to receive funding, not only from the Department of State Health Services, but also several grants due to the CDC. With this program, we go into the prison systems and have built a relationship with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice for them to identify HIV positive inmates getting ready to transition from corrections. We go in and we meet with those individuals in their individual units and start doing a needs assessment of those individuals prior to them getting ready to get out. That assessment continues once they do get released and we continue to follow them to get them linked to necessary services once they get released from incarceration.

Nadia: I had previous experience with nonprofits while I was a graduate student, but there was just something that stuck out about this agency. My graduate degree was in public health and when I was studying HIV, the stigma attached to the disease stuck out to me. I was reading about their mission statement and finding out about their programs, where it just seemed like they had a good focus on various populations that HIV and AIDS affects. When I joined the agency in 2009, it opened my eyes to the various barriers facing some of these inmates.

Were there a lot of organizations prior to 2001 trying to do similar work?

Daron: There were not a lot of agencies that were doing work specifically with the population and when we initially started, there were a lot of issues. We weren’t allowed access into the correctional facilities until we had partnered with an agency out of Houston, the Health AIDS Foundation, to do peer education in the prison. And so with that, while we was doing our training with those selected inmates, we in turn had them to also talk about our program and what we needed them to do to share the information about our program and for anyone that falls under that category. We started getting a lot of letters from inmates and at that point, we had those individuals communicate with the nurse within their facility. The nurse would be given permission to contact us on their behalf. Initially, the inmates thought that we were trying to investigate how they were providing HIV care within the prisons and we were refused access on that very fact, which wasn’t the case at all. We were basically trying to identify those individuals so we can provide the necessary support they need when they get ready to get released and once those walls were broken down, then the relationship with us and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice has been wonderful ever since then. We have been very successful in our recent efforts; identifying those individuals, going in and meeting with them and formalizing their transitional plan and effective transitional plan.

Were the inmates typically transparent about having HIV or was it difficult for them to discuss the topic?

Nadia: These individuals are not always open to sharing details about this information, but when you go visit them one on one while they’re incarcerated, they see that you are actually trying to find out information in order to help them and you develop a rapport. We try to visit them one to two times before they’re released so that they can see our faces, they know who we are, and we try to just be honest with them about what we do. That way when they’re in the free world, they have a specific person to make an appointment with. There have been a few times where an inmate won’t want to talk to a female, so we remain accommodating in that regard. I switched places with another male employee, and he was able to get the information that we needed, and I was not offended by that situation.

What’s the number of HIV cases we see in local prisons?

Daron: It ranges between 1900 to 2200 HIV positive cases for incarcerated individuals in the state prisons. This data doesn’t include the local country jails. Our focus has really been on the state prison system and the positivity rate in the state prisons is roughly about 1.6%, which is extremely high compared to the normal population. I would say roughly between anywhere from 500 to 800 people HIV positive get released each year.

What are the roughest transitions for released inmates?

Allison: I would say housing would be a hard transition. The fact that once you’re released, you may not be allowed to communicate with some of your old acquaintances and not having a social network can be challenging. I think transportation would be a big issue for people who must deal with not having their own transportation. Coming up with the funds to use public transportation can be hard, especially when they have a lot of parole appointments or meetings for their medical needs.

Daron: Those are major challenges with this population, and it depends on what their charge is and that can impact the services that’s being provided for them. If someone is getting released and they have a sex charge, it can be very difficult to find housing anywhere for those individuals. There can also be a negative stigma on anyone trying to secure employment. A lot of the employers don’t even move their resumes or applications forward when they notice that there was a sex charge.

How do you fight that negative stigma amongst employers when it comes to hiring inmates?

Daron: We’re very proactive in the communities and try to talk to employers about giving opportunities. We also try to work with representatives at the workforce commission to try to facilitate those referrals for selected individuals. While it’s still challenging, job opportunities have steadily increased. The biggest challenge is that the job opportunities available to them are roles that most people don’t want to take, like construction gigs. Even then, it seems like they continue to be penalized after serving their time and getting out. This often results in them going back to what they know, which is probably selling drugs or other criminal acts because they’re not being afforded an opportunity to gain employment.

How bad is the stigma when it comes to housing?

Nadia: There can still be stigma depending on whether the individual wants to disclose their status and that’s something that we allow them to choose. We can’t legally talk to anybody unless you say so and we must have it in writing. If we help them find housing that’s in a shared housing space, they might not be comfortable with that simply because they don’t want other individuals seeing that they’re taking medication or going to a specific medical appointment. We have an assessment called the transitional needs assessment, and we do talk about housing. We also make sure to talk about medication and if they’re disclosing their status. We sometimes visit biweekly to check up on their needs, but sometimes they prefer to figure it out on their own.

Do you ever have to talk to incarcerated individuals about not going back to previous crimes?

Nadia: We try to make sure that we find out all their needs and then we ask them real questions. Do you plan on doing XYZ when you’re released? Do you plan on going back to XYZ neighborhood? And hopefully they’re honest with us. We try to make sure to let them know that if this is something that they want to stay away from. We can help them develop a plan that fits their goals and we want to find out if they’re on any kind of parole. Any type of community supervision will affect where they can live, where they can go, or what they can see. We try to make sure that we’re very honest regarding any kind of relapses that allowed them to become incarcerated in the first place. We let them know that we are still here, even if they go back into previous crimes.

Did the COVID-19 pandemic present any logistical challenges for local prisons?

Daron: During the pandemic all the correctional facilities were shut down and were on lockdown to visitors and families. They were not allowed any visitors and basically their entire time was spent in their cells with no movement. That had a huge impact on our ability to provide services, but there was still some contact. We had to contact them via mail because we couldn’t do our regular face to face meetings with them because of COVID-19. The communication was happening through mail and of course having to depend on them to respond back to us in mail.

Nadia: To piggyback off what was said, the facilities were shut down for around a year. They opened back up this year in March with a condition that you had to submit to a rapid COVID test. You go into the facility, they swab your nose, you leave your contact information, you go wait in your vehicle and when your results are ready, they will allow you to come back in if you come back negative. Once the vaccine was more widely available, they would allow you to forgo the rapid COVID test if you provided proof of vaccination.

Was there any help from other organizations when it came to your services?

Daron: A lot of these individuals that were eligible for parole or eligible to be released weren’t being released. I can’t imagine their feelings when their release date came, and they’re still locked in a cell. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice reached out to us and they put some protocols in place to try to assist us with the process. That helped ease the tension in our ability to be able to provide these services.

Is there anything else you wanted to expand on the Free World Bound program?

Allison: Free World Bound will be meeting with people prior to their release so that when they get out, we’ll be able to help them link to medical care. We can also make sure that they have medication and any other services that they need, whether it be behavioral health, housing, or referrals for employment assistance. We want to remove those barriers that might prevent them from getting medical care. So, we’ll be doing that and then we’ll also be trying to reach their partners and associates so that we can test them for HIV and give them prevention services.